I would like to share a wonderful and inspiring post I found on

https://soulsafari.wordpress.com/

.week

Hello World. Today’s post is a longread so may I suggest to take your time.

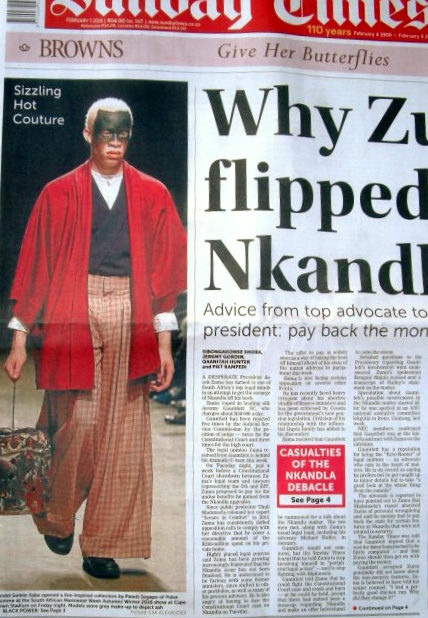

At the start of February the SA Menswear Fall 2016 Week took place in Cape Town, as in other capitals of the world. After Paris, Milan and London, the African continent sets its mark on international fashion. Fashion is flourishing as never before in Africa, a legion of ambitious young fashion designers are evolving towards national and international recognition and showing their collections to local and foreign buyers and press. The first rows are complemented by an enthusiastic young audience of bloggers and fashionistas eager to see the latest fashion.

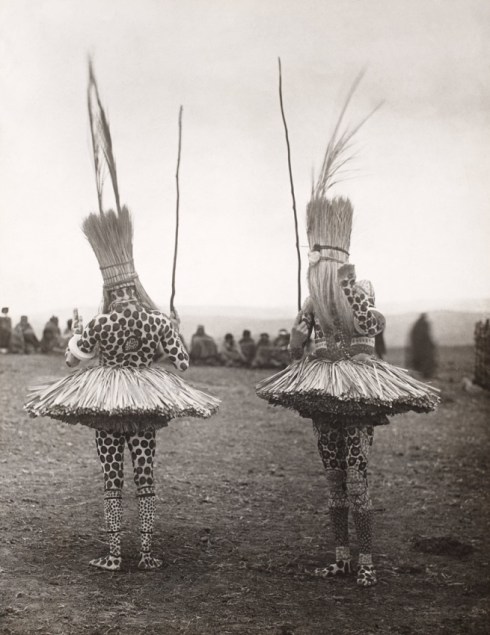

But it’s more than just expensive designer clothes or original vintage haute couture. Fashion is hot not only for style-concious hipsters but is regarded as a highly effective way to create an own identity. It is also a firm confirmation that one who dresses well has style. And the young ‘bornfrees’-the generation that was born after 1991-have style, radiate confidence and success. Besides that, African traditions and the heritage of the ancestors are en vogue.And the amazing thing is that this actually sells. A new black middle-class has the money and interest to actually buy the clothes of African designers. Design boutiques and ultra-luxurious shopping centres offer a shopping extravanga never seen before and are popping up around the big South African cities. Should you be looking for a 40’s Christian Dior jacket, a Balenciaga ballgown from the 50’s, or Jordache bellbottoms, then your retro fix will be satisfied at The Flea Market at the Market Theatre in Newtown, the cultural hub of Johannesburg.

But it’s more than just expensive designer clothes or original vintage haute couture. Fashion is hot not only for style-concious hipsters but is regarded as a highly effective way to create an own identity. It is also a firm confirmation that one who dresses well has style. And the young ‘bornfrees’-the generation that was born after 1991-have style, radiate confidence and success. Besides that, African traditions and the heritage of the ancestors are en vogue.

.

Book

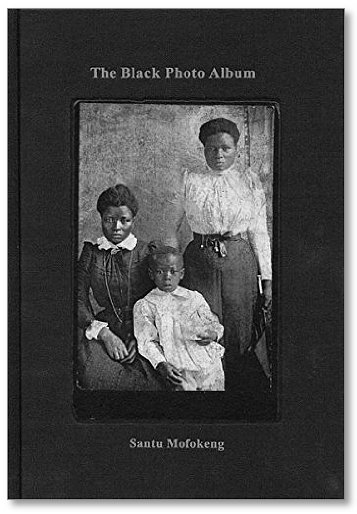

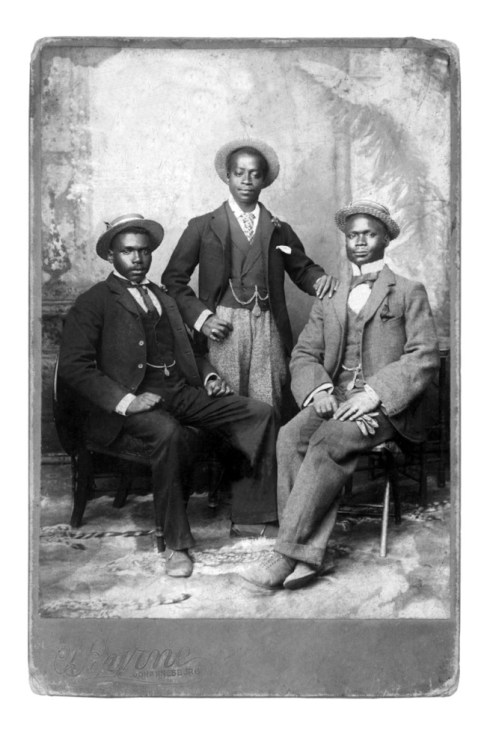

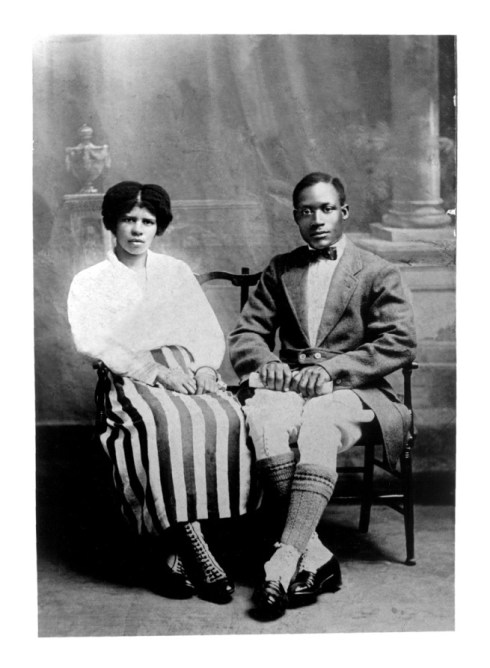

That is reflected in the book The Black Photo Album by Santu Mofokeng

DREAM BIG, ACT COOL

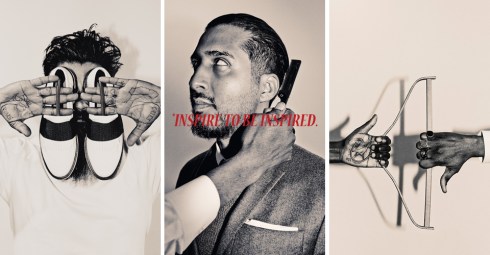

Every year The Street Cred Festival brings a buzz to Johannesburg, an excitement in street-culture that unites the hottest and cool young fashionistas and designers. Streetgangs like the Swenkas, Smarties (Soweto), Isokothan (a gang modeled after the Urhobo People of Niger Delta) show that their passion for fashion is not only obsessive by clothes but at the same time their style manifests a passive aggressive form of resistance.

Although financially limited this young generation wants to create their own look, to show the world an interpretation of Africa, a tribute to their ancestors while looking forward to the future. It is hopeful and positive. What is Africa, Who am I as an African, those are the big questions that engage this new generation. Bloggers like Sartist reflect the search for a new horizon of fashion and dopeness.

.

LES SAPEURS & NYC GANGSTA STYLE

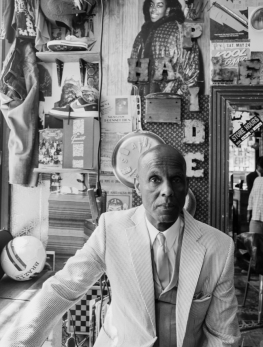

Each new movement has obviously predecessors. Les Sapeurs became somewhat of a household name in Congo in the 60’s with their brash dandyism. In New York it was designer Dapper Dan of Harlem who created the flamboyant look and style of rappers like LL Cool J and other heroes of the early hip hop scene in early 80’s.

Each new movement has obviously predecessors. Les Sapeurs became somewhat of a household name in Congo in the 60’s with their brash dandyism. In New York it was designer Dapper Dan of Harlem who created the flamboyant look and style of rappers like LL Cool J and other heroes of the early hip hop scene in early 80’s.

Right on 125th street in Harlem USA, sat a custom high-end clothing boutique owned by Mr. Dapper Dan. Before Kanye, Juelz, Fabolous and some other well known rappers wore Gucci and Louis Vutton, Dapper Dan in the 80’s and 90’s planted the seed for fashion in the hip hop culture. He created one of a kind customized high-end clothing that incorporated highly recognizable accessory logos like those of Gucci and Louis Vuitton, featuring them in non-traditional ways. His pieces were sold for thousands of dollars, and created a sense of what’s cool, what’s new in the streets and ‘in hip-hop’.

The designer describes his way of working as ‘sampling’, an unique interpretation of mixing existing designs and logos with his own interpretation. Dan Dapper ” I opened my workshop in ’82. First I would take little garment bags by Louis Vuitton and Gucci and cut them up, but that wouldn’t suffice for complete garments. So I said, “I have to figure out how to print this on fabric and leather.” I went through trial and error. I didn’t even know we were messing with dangerous chemicals—the U.S. government eventually outlawed the chemicals I was using. We made these huge silk screens so I could do a whole garment. A Jewish friend of mine helped me science out the secret behind the ink, and that was it.”

FAVORITE CREATIONS: The “Alpo Coat” [for drug dealer Alberto Martinez] and the Diane Dixon coat [for Olympic athlete Diane Dixon]

Diana Dixon wearing the “Diane Dixon” coat by Dapper Dan

Diana Dixon wearing the “Diane Dixon” coat by Dapper Dan The “Alpo Coat”

The “Alpo Coat”

His designs specified the look of hip-hop artists, sporters and those incurred by gangsters. “Gangsters. That’s who I grew up with. Middle-class blacks couldn’t accept what I was doing—you had to be of a revolutionary spirit. Who would be more like that than gangsters? And who would have the money? Hip-hop artists didn’t have any money. They used to wait until the gangsters left the store before they could come in and ask what the gangsters wore. Everybody follows the gangsters. The athletes came before the hip-hop artists. Mark Jackson, Walter Berry. I’ve got pictures of NBA players that I can’t even remember their names. The athletes had money earlier that the hip-hop artists.

.

AFRICAN DESIGNERS LIGHT UP THE CATWALK

Ozwald Boateng is a London fashion designer of Ghanaian descent and co-founder of Made in Africa Foundation, which supports and funds studies for large-scale infrastructure projects across Africa.

Boateng is known for his classic British menswear, done in warm colors. He is considered one of the most successful designers of men’s fashion in recent years. His big break came in 2005 when he worked as designer for the French fashion house Givenchy and dressed actor Jamie Foxx for the Oscars.

His first show in Ghana caused a small revolution. Just like in 2013 during NYC Fashion Week where Boateng showed mainly African prints processed in classic men’s suits on black models. Boateng’s explains his vision on style; “Colonialism has done little good for Africa but it brought the typical Western sense of style and elegance to Africa. Mixed with local traditions this sensibility created a truely new African identity.”

Ozwald Boatang

During the same week in New York, South African born designer Gavin Rajah brought the fantasy element of fashion back to the runway with creations that were eclectic and high glamour. Again black models ruled the catwalk.

.

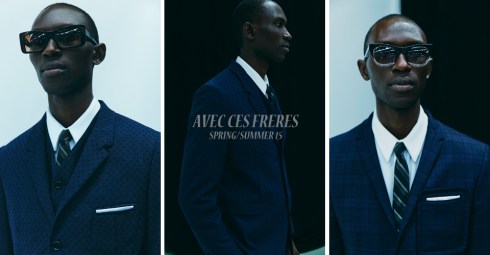

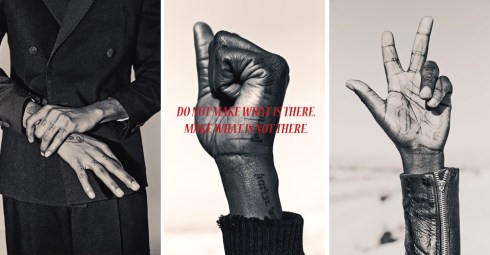

DO NOT MAKE WHAT IS THERE, MAKE WHAT IS NOT THERE

Is the motto of label ACF (Art Comes First/Always Cut First). ACF is an exciting innovative concept that typifies the New Black Dandyism.

In their vision a modern-day gentleman stands for Energy, Style, Power and Pride.

Lambert and Maidoh have worked to vitalize this simple notion in a fresh travel-friendly wardrobe crafted with intelligence, curiosity and good intention.

.

BLACK POWER

Dark Models dominate World’s Fashion Weeks catwalks…

Jimi Ogunlaja

Jimi Ogunlaja Jimi Ogunlaja

Jimi Ogunlaja Akuol De Marbior, backstage at Max Mara

Akuol De Marbior, backstage at Max Mara Akuol De Marbior

Akuol De Marbior

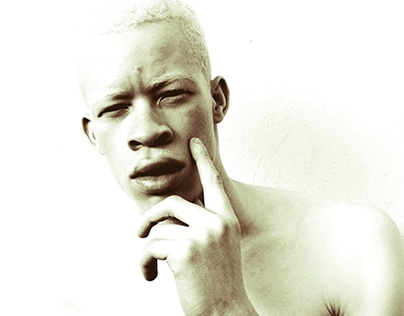

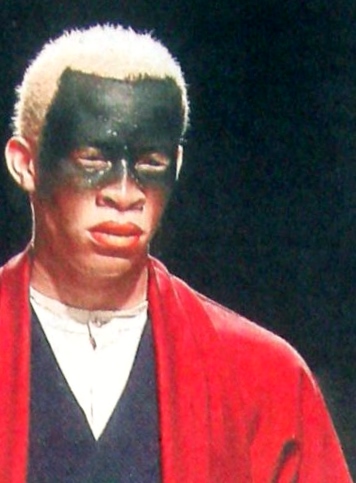

There are 50 shades of grey, and perhaps even more shades of black. And the blacker the better as South African designers scramble for darker-hued models who are regarded as ‘edgy and classy’. About half the models at the South African Menswear Autumn/Winter 2016 in Cape Town were very dark. They walked for designers including Craig Jacobs, Julia M’Poko of Mo’Ko Elosa and Jenevieve Lyons.

Popular on local runways is Jimi Ogunlaja, a Nigerian-born model and the face of 46664 Apparel, who has been walking ramps in South Africa for brands including Fabiani, Carducci and Craig Port since 2008.

Tami Williams at Balmain

Tami Williams at Balmain Maria Borges at Balmain

Maria Borges at Balmain

During the Paris Fashion 2016 Week black models also graced the Balmain Fall 2016 Ready to Wear catwalk, although the look and wide choice of models was based on the now platinum Kim Kardashian West. Her husband Kanye was sitting front row. His fashion-show-slash-record-listening-slash-party in New York last month drew 20,000 New Yorkers into Madison Square Garden on a freezing Thursday afternoon. The premiere of Yeezy Season 3 and stream of his new album, The Life of Pablo, proved to be the event of the New York Fashion 2016 week—with people lining up hours beforehand to enter. Young, old, invited or not, Kanye fans patiently waited for the doors to open. And once they did it was madness. The power of commercial streetstyle!

Kanye West’s Yeezy Season 3 Extravaganza

Kanye West’s Yeezy Season 3 Extravaganza

Lupita Nyong’o, one of the hottest black actresses of the moment walked onstage of the Late Night With Seth Meyers-talkshow in a tomato red Balmain power suit. Lupita Nyong’o is a Kenyan actress and film director. She made her American film debut in 2013 in Steve McQueen’s historical drama 12 Years a Slave. She won an Oscar for her supporting role as Patsey. But movie stars, popstars or fashion designers with African roots are not the only forces to dominate fashion in 2016, the biggest influence remains the First Lady of the USA, Michelle Obama.

Lupita Nyong’o wearing Balmain

Lupita Nyong’o wearing Balmain Lupita Nyong’o on the cover of Vogue

Lupita Nyong’o on the cover of Vogue Lupita Nyong’o on cover of Dazed &Confused

Lupita Nyong’o on cover of Dazed &Confused

.

US First Lady Michelle Obama 2016

US First Lady Michelle Obama 2016

.

Special thanks to:

https://soulsafari.wordpress.com / for sharing this post written by eedeecee

.

.

http://www.safashionweek.co.za

Sources: The Guardian , les Sapeurs; battle of the dandies, The Sunday Times 7th February 2016