From sudden Fame to harsh Criticism

In many ways Corinne Day memory is shadowed by the moment of her greatest good fortune: her spotting of a Polaroid of a gangly Croydon teenager among the files of a London model agency in the spring of 1990. She brought a photograph of the 14-year-old Kate Moss to Phil Bicker, the visionary art director of the Face magazine, then the single most influential style magazine in Europe. Back then, Bicker was busy reinventing British fashion photography as a gritty, altogether less glamorous form. He had gathered a bunch of young and ambitious photographers, including Glen Luchford, David Sims and Nigel Shafran, all of whom became successful in the fashion and art world. Corinne Day was perhaps the most temperamental, a feisty, self-taught, model-turned-photographer with attitude to burn.

“It was an exciting time because we were making up the rules as we went along,” says Bicker, “I saw the same thing in Kate as Corinne saw, that she represented something very real: the opposite, in fact, of all the unreal high glamour of fashion. I sent Corinne and stylist, Melanie Ward, down to Camber Sands to do a shoot with her.”

The cover of the July 1990 issue of the Face gained iconic status in the fashion world and beyond. On it, the young Moss, who appears to be wearing no make-up, grins like an excited and slightly gauche teenager from beneath a headdress made of fabric and feathers. The cover line announces “The 3rd Summer of Love” and promises features on the Stone Roses, Daisy Age fashion and psychedelia. The summer – and the decade, and the style-obsessed world in which we now live – had found its face.

. .

.

Inside, Kate Moss cavorted on Camber Sands in hippy-style clothes, sometimes topless, like a girl who could not quite believe her luck. Bicker is quick to point out that, although the fashion shoot seemed casual and unstyled, it was, in reality, the opposite. “It looked natural and simple but it was carefully constructed to look like that. In fact, as I recall, I sent them down there two or three times until they got it right. Kate hadn’t been modelling for very long but, even in her awkwardness, she had that thing about her that Twiggy had in the 60s, a freshness that matched the times.”

Juergen Teller, one of Corinne Day’s peers, and now the most globally successful photographer of all the young iconoclasts of that time, concurs. “I loved Corinne’s first photographs of Kate. They had that end-of-summer feel and seemed very fresh and almost naive, but in a good way. To me, they were her best photographs.”

The 3rd Summer of Love

.

Revealingly, neither Kate Moss or her model agency were pleased with the photographs, finding them too raw and unadorned. Corinne Day had brought her own experience of being a model into the shoot. She later said, “It was something so deep inside, being a model and hating the way I was made up. The photographer always made me into someone I wasn’t. I wanted to go in the opposite direction.”

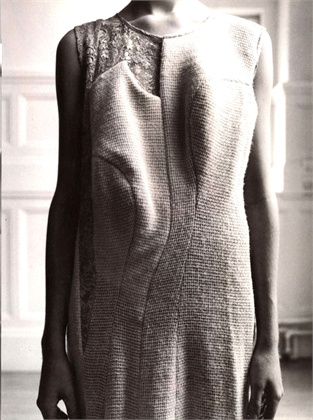

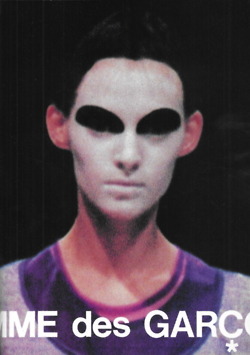

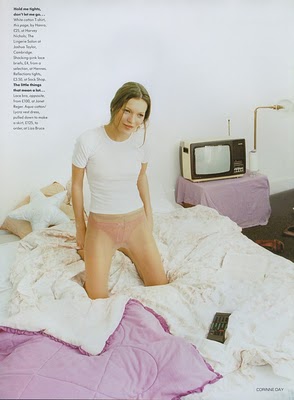

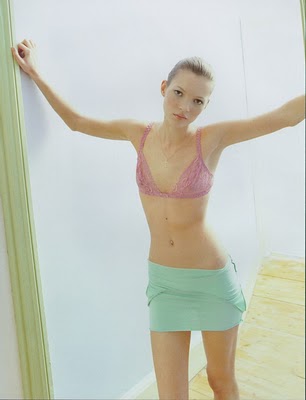

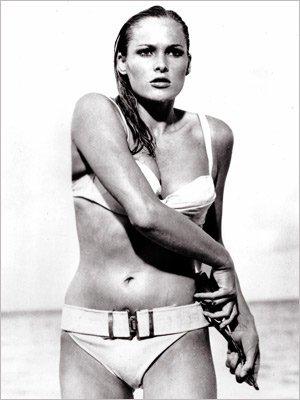

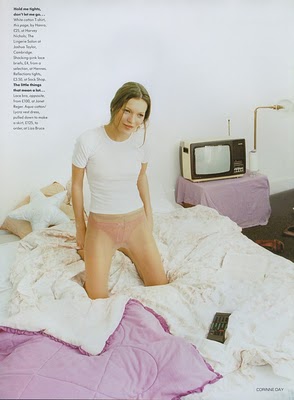

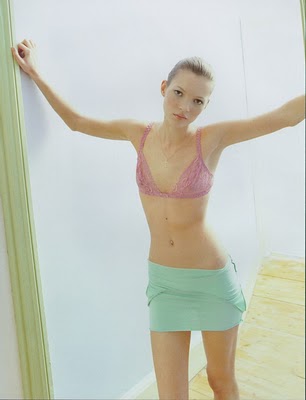

But the next time Corinne Day impinged on the public consciousness, that freshness had been replaced by a darker, harsher vision. In 1993, she photographed Kate Moss for a fashion shoot for British Vogue, Under-exposure. In it, the model looked strung out and sad, dressed down in baggy tights and stringy underwear that exacerbated her skinniness. Again, the photographs were a reaction to the glitzy unrealness of the fashion photography that Vogue usually featured, but here the extremity of Corinne Day’s vision provoked outrage and hysterical headlines about the glamorization of anorexia and hard drug use.

The terms “heroin chic” and “grunge fashion” were born and bandied about in the tabloids. By then, the troubled and troublesome photographer had burned too many bridges in the fashion world and, more problematically, was actually living in, and intimately photographing, a bohemian milieu defined by hard drug use.

Under-exposure

Corinne Day later said that she took the shot above on a day when Kate had been crying after a fight with her then-boyfriend, resulting in the vulnerability that turned this into one of the most iconic and controversial images produced in the 90s (on, of course, the charge that Kate was too thin, heroin chic,etc). It’s the most reproduced image of the entire editorial, but the clothes (pink Liza Bruce vest and Hennes- now known as H&M- chiffon knickers) are rarely remembered, or credited. I have the picture on my Wall of Fame. The vulnerability, innocence & simplicity of the image made it iconic picture to me too.

Start photography

Corinne grew up in Ickenham with her younger brother and her grandparents. She left school aged sixteen and worked as an assistant in a local bank. After a year at the bank she became an international mail courier. It was during this period that someone suggested she try modelling – she worked consistently as a catalogue model for several years. In 1985 she met Mark Szaszy on a train in Tokyo – Mark was a male model and had a keen interest in film and photography.

During an extended trip to Hong Kong and Thailand, Mark taught Corinne how to use a camera and in 1987 they moved to Milan. It was in Milan that Day’s career as a fashion photographer started. Having produced photographs of Mark and her friends for their modelling portfolios, Corinne began approaching magazines for work.

From Fashion to Documentary

Corinne retreated from fashion work in the wake of the heroin chic debate, instead choosing to tour America with the band Pusherman and concentrate on her documentary photography. She also undertook work photographing musicians, including the image of Moby, used on his 1999 album Play.

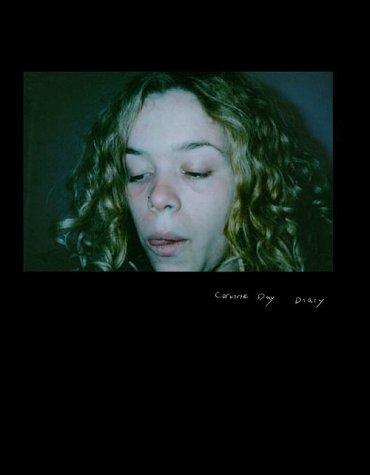

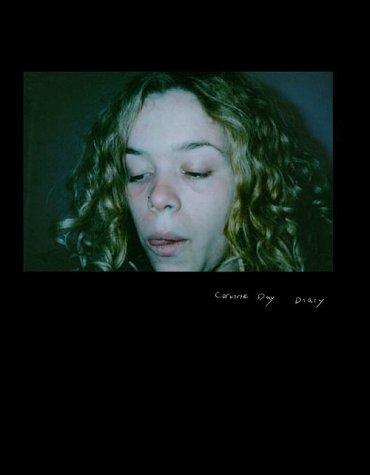

Her autobiographical book, Diary was published by Krus Verlag in 2000, and contained frank and at times shocking images of Corinne and her friends. The images in Diary featured young people hanging out, taking drugs and having sex, and have been compared to the documentary realism of Nan Goldin. Coinciding with the publication of Diary, Corinne had two large-scale exhibitions in London in 2000.

Diary

Diary also records the dramatic events of the fateful night in 1996 when Corinne collapsed in her New York apartment and was rushed to Bellevue hospital. There, she underwent an emergency operation for a brain tumour. She insisted that Mark photographed her, even in the moments leading up to her surgery. She looks dazed, helpless, disoriented. “To me, photography is about showing us things we don’t normally see,” she said later, “Getting as close as you can to real life.” The book’s final picture is of a beach strewn with beer cans: a glimmer of hope, and yet a tarnished one.

After her initial illness, Corinne made an uneasy truce with fashion photography. She abandoned her raw, edgy style for something more traditional in the fashion shoots she did for, among others, British, French and Italian Vogue, Arena and Vivienne Westwood.

Corinne’s tumour returned in 2008 and a campaign called Save the Day was started by her friends to pay for treatment in a clinic in Arizona. It raised £100,000, much of it from the sale of signed, limited-edition prints, including several of Kate Moss that were signed by the model and the photographer.

Corinne Day, who died 27 August 2010 , will be remembered for transforming fashion with her pictures of the young Kate Moss for the Face.

Most information for this post from: The Observer, article by Sean O’Hagan & Wikipedia

Official website Corinne Day: http://www.corinneday.co.uk/home.php